We conclude that if higher education in the United States is to be successful in the twenty-first century, it needs to be sharply REFRAMED. Pervasive issues of mental health and belonging must be addressed; extensive onboarding is needed with respect to the centrality of the academic educational agenda; any goal that is not strictly tied to learning needs either to be excised or to be clearly interwined with the academic agenda. (xvii)

This book “The Real World of College” is a deeply researched call to action for post-secondary institutions, and a clear cautionary call out to K-12 institutions as well. Looking downstream, as a K-12 education leader, Fischman and Gardner do an excellent job of painting the landscape, providing insights, recommendations and examples of how students, faculty and administrators can better serve our students as we prepare them for post-secondary life. By the end of the book – and the end of this blog – a circle is drawn that brings us back to how to REFRAME the purpose of education – both post-secondary and K-12.

You would be interested in this book if you were looking…

(1) To better understand the challenges and opportunities facing students in post-secondary AND how to support them as a K-12 educator

(2) For mental models of how faculty and students approach their lived experiences in post-secondary AND how these interact when misaligned

(3) Into the trends and possible futures of post-secondary education for students AND how you might best prepare them

(4) To explore the “WHY” of education and possible future direction of post-secondary education AND how K-12 education can play a role in making it a better future

The 4 Mental Models and HEDCAP:

This book reads really well for a deep and long research project – it does! And it is important to understand the different conceptual frameworks they built in order to understand their analysis and conclusions:

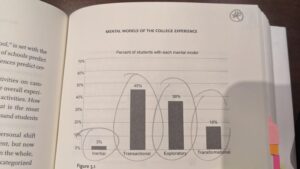

The authors have taken all their data and created 4 mental models of how students, faculty and families approach post-secondary education: (pg. 121)

(1) Inertial: not thinking too much about being in post-secondary, they are simply following a path, and not engaging in many opportunities, nor exhibiting much aspiration

(2) Transactional: Going to college because it is a hoop to jump through, a required step to get them to the next step.

(3) Exploratory: Intentionally taking time to learn about diverse fields of study, try new activities, broaden their perspective, and their networks of people from diverse demographics in order to better understand themselves.

(4) Transformational: Reflecting about and questioning one’s own beliefs and values with the expectation, and aspiration to change themselves for the better

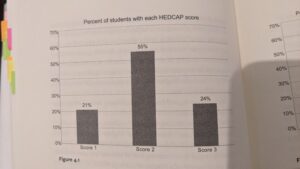

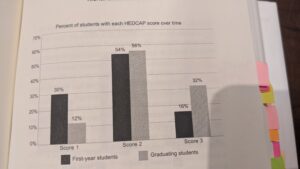

The authors also developed HEDCAP (Higher Educational Capital) to denote the extent to which an individual displays the kind of thinking one would reasonably expect of a graduate of an institution of higher education. It takes into account grade point averages, academic honors, but the authors were most interested in “…ways in which student think, reasona nd reflect on signifigant matters. Put succinctly, HEDCAP denotes the ability to analyze, reflect, and communicate on issues of importance and interest.” (Pg. 79)

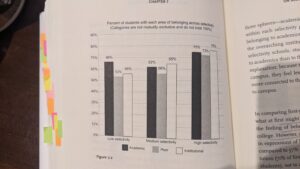

They are able to take this data and compare HEDCAP scores between first year and graduating students:

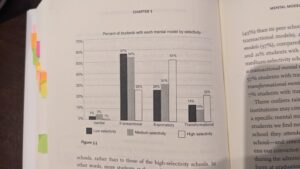

When they take these two together, they then apply them to different campus ‘Personas’: School of low selectivity to high selectivity. When put together, you can get some incredible narratives:

In this way, this book paints an incredible picture from thousands of interviews across numerous campuses to draw conclusions about challenges, opportunities and future directions.

Whatever our method, our metaphors, our madness, or our mode of reference, we did what we set out to do – we carried out over 2,000 one-hour interviews on ten campuses. That’s a lot of words, a lot of pages, and a lot of recording. Wendy conducted perhaps 400 interviews, and Howard conducted perhaps 250 interviews. We have both read more than 2,000 transcripts, sometimes more than once. (pg. 54)

Mental Health and Wellbeing:

The quotationI chose to begin this post struck me because of the word REFRAMED, and it’s connection to the work of Stuart Shankar. In the book, the authors were surprised by the overwhelming centrality of mental health:

While we had not anticipated that health would be a major topic of this book…it is essential that we address it. If students are preoccupied and distracted by overwhelming personal issues – whatever the problems might be – it is very difficult for them to focus on learning, let alone on possible transformation of their minds. (172)

The authors began this study long before the pandemic hit, and so wellbeing was not on their radar when they set out; however, it quickly became apparent that mental health and wellbeing were central to the experience of students and their mental models, of education.

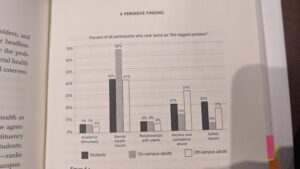

Wellbeing is connected with belonging in this research, and (rightly or wrongly) they are interwoven in how the questions were develop and asked of the participants. The results are incredibly telling:

They delve deeply into this work and were able to find some nuances:

…We find that students who rank mental health as the biggest problem are significantly more likely to have a transformational mental model than to have a transactional model. (pg. 192 – bold is mine)

While there may be many explanations, the causes are something that we, the reader, the parent, the educator can wrestle with. This book presents these provocations for us, but solutions come later.

Belonging was pulled out and addressed on its own, which I thought was really telling. They drew upon a range of scholars to assess and measure belonging across academic, peer and institutional (Pg. 205)

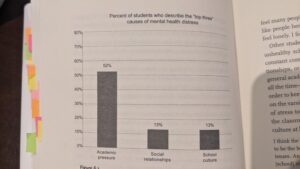

The top three causes of mental health are also explored: “Perhaps not surprisingly at this moment in history, when studetns discuss academic pressure as a cause of mental health the most frequent explanation focuses on achieving external measures of success – securing a high grade-point average, etc…” (pg. 179) This is a very transactional model, present across all campuses.

I would also note that for students, perfectionism is very much a part of wellbeing. In their study this was most evident at highly selective schools:

At least two possibilities arise (1) students with a strong sense of ‘internal perfectionism’ are attracted to a particular type of school and student body, and / or (2) students who attend these [highly selective] schools develop a heightened internal drive over the course of the college experience. (Pg. 186)

The Black and People of Colour Experience

For many in the study, as the charts above indicate, the purpose of them going to College and University is for exploratory or transformative experience. Participants in the study talked about diversity in both positive and negative ways throughout, and most of the comments focused on demography – specifically race and gender. Comments were largely positive in terms of meeting different people from different demographics; however, many described problems. (pg. 226)

Students with complaints [about intolerance and lack of empathy] also believe that their peers don’t know how to conduct productive conversations about issues of race, which leads to frustration, rather than to an enhanced perspective… (Pg. 227)

This helps to understand HOW and WHERE we might do DEI work with our students who are in K-12.

When the authors take on the massive amounts of data, they are able to weave together narratives that clarify and amplify major issues and trends on campus across a spectrum of students. This is invaluable for those of us working upstream in K-12 education.

Main Institutional Issues & Recommendations

The authors, in the latter half of the book, move to a “So What. Now What?” approach for next steps. They identify three main issues facing institutions that are preventing them from really and truly enhancing the student experience and providing an education that will uplift our students into productive, empathetic, contributing people:

(1) Mission Sprawl: All institutions have a mission statement; however, there are a multiplicity of mission statements from different sub-departments within the organization: “It is a rare school that has a single mission statement and adheres to that mission in deed as well as in word” (Pg. 240)

(2) Projectitis: “We coined the term “projectitis” to describe a frequent and distinctly unhelpful ramification of mission sprawl….” It is the proliferation of different projects (such as new buildings, new DEI initiatives, etc…) that are begun, but never accounted for / curated effectively / tied to mission well. This results in a lack of prioritization and diffusion of impact across all programs.

(3) Misalignment: There are, throughout the study, a good amount of examples where ideas, perspectives and views are misaligned: “A recurring example: the difference between the views of on-campus adults, on the one hand, and those of students and off-campus adults, on the other. Such misalignments can create confusion, engender misunderstanding, and institute repair strategies that may or may not be effective.” (Pg. 243)

No doubt, these three challenges can be recognized by some of us in K-12 education. So it is heartening to know that we can actually take much from this book to support our own work, because, once identified, the authors begin a series of recommendations for institutions that we, in K-12 can learn much from.

The authors recommend two key strategies:

(1) Onboarding: I love this recommendation because it speaks to bringing all members of the community together around the missions. That all new projects must be tied to mission and how it will help realize that mission in our students. “We should never take onboarding for granted – it’s not the job of students or parents to figure out the mission of higher education: such articulation is clearly the responsibility of the leadership, faculty and staff of each institution.” (pg. 247) This reminds us to be clear and transparent in our communications about how the WHAT and HOW of our school is living out the WHY of our school.

(2) Intertwining: Missions and projects, initiatives and goals “…need to be thoughtfully intertwined into the curricular, cocurricular, and other ‘messaging’ activitites and platforms in the school. Moreover, there should be measures of success of the intertwining, as well as corrections – or even scuttling – if it is not working.” (Pg. 247)

Great Quotation from this section:

In this section of the book there are powerful messages to support HOW institutions should onboard and intertwine successfully and I loved a few of them, which I will highlight here:

(1) On the goal of liberal arts education:

The goal of each interdisciplinary learning community is that every student should develop an identity as a student on campus and as a contributing member of the local community. (Pg. 257)

(2) On curriculum and pedagogy:

Not only should there be copious assignments and projects where cheating is not possible. Far more important, students should be asked to carry out work that is mind-expanding; projects and problems that stimulate them to take on new roles and try out new ways of thinking… (Pg. 261)

(3) On the Educator Mindset:

If you have followed [the thread of our work here] you may be saying, “Aha, that’s the problem. Our student do not want to stretch” That may be true, but it’s very different from saying “Out students cannot stretch.” They can! They should! It’s your job, indeed your calling, as trustees, faculty, administrators, counselors to show how you have stretched… and help these students do the same

The authors then highlight several examples of programming already in effect to support, strengthen and amplify these calls to action

Messages to Different Audiences

What brings this incredible work home for me, are the targetted messages to the readers: to students, families and educators. They encourage parents and students to consider the big WHY to post-secondary education, they bust some myths, and bring to prominence different ways to navigate the 4 years, including a gap year:

The faculty and leadership of your school owe you their best efforts to provide a good and rounded edudation. But even if they strove day night and day, they could not merely hand you excellent education on the proverbial platinum platter. You need to make commensurate efforts . And importantly, if your own efforts are not enough, you need to reach out for help – or perhaps take time off until you feel you have the requisite motivation. For many of us, a gap year (or even two or three) can make a significant, positive difference. (Pg. 294)

There are great messages to parents on how to balance out the pressure and stress, by ensuring that your child(ren) understand and are aligned with the WHY of post-secondary education. In their research they found that students feel immense pressure on them, from their parents, that post-secondary is transactional, i.e. get a job!

So [for parents] it is worth going out of your way, as vividly and specifically as possible, to foreground [for your children] the important non-vocational aspects of college: the exciting and mind-opening courses, the travel adventures, the amazing speakers and campus visitors, etc…” (Pg. 297)

Many of these quotations above, and other wisdom shared throughout, will certainly resonate with educators that believe in students willingness and desire to learn; it will resonate with those who believe that students can develop independence and should, through non-catastrophic failure.

But what should resonate with all educators comes from one of the final sections, entitled “Message for Educators of K-12 Students”:

Ultimately, we should aspire to have student entering college who understand the primary purpose of higher education…Unfortunately, rather than preparing for college, getting into college has become the focus of many high schools…Students should view college as the expansive opportunity of a lifetime, rather than a reward for a job well done in high school. (Pg. 298)

This part is gold for K-12 educators to help reframe the purpose of high school and the ultimate opportunity of college. And so we have come full circle with how this book, through research, mental models, campus ‘personas’ and data analysis provides wisdom and provocations for K-12 educators on how best to prepare our students for the here and now, and what might be.

Thanks for this! @gnichols SO much to think about