How might we improve student writing by leveraging our innate desire for social connection? Today on the podcast, I make a case for why you should consider including journalistic writing in your class.

A young person that I am close to, let’s call her Annie, is really struggling with school, especially since the onset of this pandemic. When we talk about what she finds challenging and what her teachers might do to improve the situation, her response, I believe, reveals a larger systemic issue in schools today: she wants to be able to talk more with her friends, she is frustrated with the number of hours she is expected to sit still and stay focused, and she is deeply bored with assignments that just involve reading things and answering short questions about what she reads. Annie is not unique in the things that she is frustrated about in regards to school. She is asking for more collaborative, social learning. She is naming the fact that the curriculum does not need to be limited to the four walls of her classroom. She is yearning for powerful, authentic learning that has a purpose beyond a grade. Annie is struggling and I don’t think she needs to be. She is bright, capable, thoughtful, curious…and in many ways the system is failing her.

In this episode today, I make a case for why teachers––and not just English teachers––should consider using journalistic writing in their programs to transform writing, student engagement, and purpose in their classrooms. This is not a typical kind of show where I interview a guest about their work. Instead, today we dive into the research about writing, social discourses, and journalism. I offer some ideas for what teaching writing with journalism can look like in your classroom. My intention is that after this episode, you keep this genre on your mind and consider working with it in a future unit or share this episode with a colleague and collaborate together on something in your own practice.

Background Terms and Backstory

Before we do any of this though, let’s take a moment and pause to make sure we are all on the same page when I am using the term journalistic writing. What is that? When I say “journalistic writing” I am referring to non-fiction, factual, researched, news article writing. The kind of writing that I focused on with my students are the kinds of pieces that you might find in the front section of a newspaper: they are written in 3rd person perspective, they use short paragraphs, they use direct quotes from interview sources, the facts included are from high quality / verifiable sources, and they centre around topics that are deemed “newsworthy.” These pieces of writing aim to include multiple valid perspectives on a topic and the writers crafting these pieces strive to be aware of their own identities and biases and how these may impact their reporting.

For me, this journey with journalistic writing started in 2017. I was coming back from my first maternity leave and was inheriting a grade 8 English class (I had taught grade 7 English and Social Studies before having my first child). The teacher with this grade / subject before me had taught a journalism project for many years. I always admired and fangirled over this project when I was witnessing it from afar. I loved the authenticity, the challenge, the real world connections and this brand of non-fiction storytelling. So when I stepped into Grade 8 English, this was what I was most excited about; however, the first year I did this journalism project it bombed. Like hard. I’ll get into those early failings a little later.

Over the course of several years of slowly improving this project, I became obsessed with the process of young people writing about topics that truly mattered to them. I loved how it positioned young people to consider multiple viewpoints (including their own), engaging in interviews with real human beings who existed outside the sphere of our classroom, and publishing their work for others to read. I have seen young people change because of the things they have written, I have experienced the school communities shift because of their writing, and I have seen young people engage more fully with the writing process and in turn improve their skills.

Now that I am engaging more with research about student writing, I see that there was a key ingredient present that hugely contributed to this writing experience “working”: it is a social writing discourse!

Social Writing

A social writing what now? Ya, I feel you. I thought the same thing when I was first reading about this. I’ll back this train up a touch and introduce you to Roz Ivanič. Picture a friendly looking white woman with white hair, kind eyes, and a cute, blunt bob haircut. Roz is a scholar based out of the U.K. that has identified seven main ways, or discourses, of writing that should be included in all writing curriculums. These include skills, creativity, process, genre, thinking, social practices, and sociopolitical discourses. While all six of these discourses are important and worthy of explanation, for the purposes of this episode, only two––social practices and sociopolitical discourses––will get deeper explanation. The social practices discourse says that writing is a communal experience, and that writing instruction cannot be removed from social contexts. The sociopolitical discourse takes this further by critically examining why genres and styles of writing exist the way they do, and it sees writing as a vehicle for constructing more powerful identities for marginalized people. Roz did not invent the idea of writing being a social practice. Rather, she is saying that how we teach writing cannot just be focused on the grammar (the skills discourse) or the metacognitive routines that students engage with (process discourse), but that a well balanced writing program includes many modes of writing instruction. And this is likely not surprising to you (or to my friend Annie that I mentioned earlier) but what may be surprising is that: the social practices discourse and sociopolitical discourse are both dramatically under-represented throughout writing ministry curriculum documents in Canada. So no wonder Annie is struggling: her teachers may not ever be pointed to including these ways of learning in their programs and her teachers may never have been taught how to teach in a way that supports these discourses!

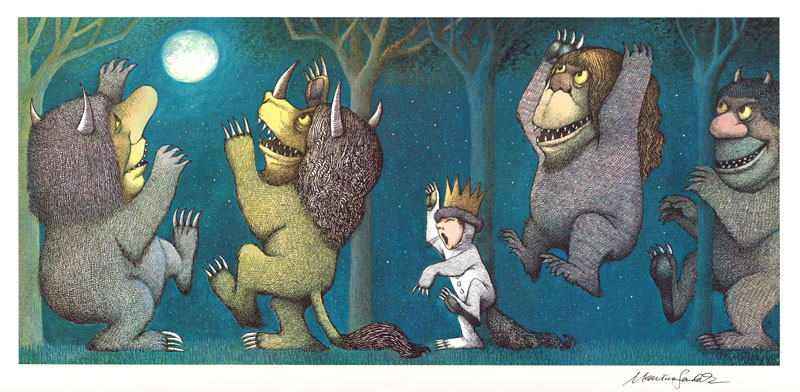

So back to my journalism unit. How was this a form of a social writing discourse? Well, there actually many aspects of this learning experience that tie it in to a social writing practice. And of course I made an acronym for us to easily remember it: do remember in the book Where The Wild Things Are and the part where they have that epic dance party? Do you remember what it is called? Yep, the wild rumpus. So to remind us that social writing is kind of like that, journalistic writing is social discourse because is it is RUMPUS. R stands for Researching Through Interviews. U is Unpacking Identities. M is for Mentoring. P stands for Publishing. U is for Useful Community Collaboration. And finally S is for Stategic Feedback. My friends, let the wild rumpus start!

R: Researching Through Interviews

The way that students researched about the topics that mattered to them was not just by researching on the internet or reading books. To ignite that enthusiasm for learning, it really makes a huge difference when young people are researching topics that they choose and that matters to them. In the research, this shows up again and again as something that makes the learning matter and important. You have to start with the interests and passions of the people in your class. In different years, I had given some broad parameters for how students could select their topics: one year I had students pick something that related to the city of Toronto somehow (we were engaged in a big, year long city investigation) and in another year, their topics had to somehow loosely be connected to the idea of sustainability (either social, environmental, or economic). When students care about their topics, finding sources to interview becomes a deeply authentic, slightly scary, and hugely motivating social aspect of the learning. Ideally, these interviews are conducted in real time––either in person, over the phone or over something like Google Meet or Zoom––so that students get that real-time feedback when their questions don’t make sense, they are not getting enough detail from their sources, they are not getting the kinds of quotes they need, or it is clear that they are not talking to the right person. Social learning still takes place over email, but in my experience, the “fear factor” of sitting down and talking to your friend’s mom about her small business is much more powerful than sending an email and waiting for a reply. In the research, young people report that until they were required to interview people for a connected learning project, they had never even considered this as a form of research! Even just the novelty of it alone should be a reason for us to include interviewing other people as an aspect of our writing projects.

U: Unpacking Biases

Something that arose in response to my first epic failure of my journalism unit was the need for students to understand their own biases. If you have been paying attention to the world, you have likely noticed that there is increasing distrust of the media today. Yes, Trump has caused this in part, but this has been going on long before 2016. Traditional news reporting claims to be objective, but is it possible to choose stories, research, or write without being influenced by our backgrounds, identities, and biases? Probably not, I think. What if instead of trying to erase our biases, we were more aware of them as writers and could consider them more carefully in our attempts at sharing the most accurate version of the truth? So something that I did, that was echoed in the research, was I had my students try to identify their personal beliefs about their topic. Then, if their final article only captured these beliefs, it would be more clear that there may be missing perspectives that could be included.

Another teacher had her students “take a stand” to help identify biases prior to writing and research. Students were given a variety of controversial issues and they had to try and articulate what they personally believe about these issues. For example: Should the government be doing more to reduce carbon emissions? Should policing programs be defunded? Is enough being done to teach anti-racism in schools? Then, at the end of the project, students reflected on their views captured when they were asked to “take a stand” and not surprisingly, their views had evolved and became increasingly nuanced as they researched more about the issues and heard from multiple perspectives. This, afterall, is a huge reason why journalistic thinking is a valuable tool for young people: it expands the way we see the world and encourages empathy. When we try to understand another’s perspective (whether by interviewing them or by hearing where they stand during a pre-writing practice), we are tapping into those social discourses and making the learning stronger. Nobody knows alone.

M: Mentorship

The next idea that emerged from the research, I am a little obsessed with. This idea is so simple, so obvious that you are going to wonder why it isn’t used more in writing classes and it is this: reverse mentorship. Reverse mentorship is not undoing mentoring or being a bad influence on writing (wouldn’t that be something?). This is a strategy that pairs recent journalism school graduates with classroom teachers to support the writing in the classroom. It is essentially a classroom teacher consulting with a budding journalist to help inform the writing the students are doing. The teacher knows the students, the classroom, and the pedagogy. The recent journalism school graduate knows the genre, the discourse community, and the process of writing. The teacher is of course mentoring the students and the journalist is mentoring the students…as well as the teacher! It has been a well known dirty little secret in education that teachers do not feel capable of teaching writing to their students and that students are only writing about 25 minutes a day in all of their classes. Let’s just take a moment and pause on that. 25 minutes a day of writing! So as a profession, teachers of writing need more mentorship, support, and training. Reverse mentorship may be a way to do that which is aligned with the social discourses model of writing. We learn through social relationships, so if a teacher and a journalist can collaborate together about student writing, the teacher’s writing instruction in regards to this one genre can improve, the student writing can improve, and the journalists can establish more social connections with members of their community. It is a win for all.

In my own practice, I experienced a taste of this. I don’t know if I would call it reverse mentorship, but rather just straight up mentorship, as the mentors I worked with were not younger than me. The first instance, I had a parent of a student who worked in journalism in a fairly public facing way. When my first project didn’t work so well, we had a conversation and he provided some insights about what I could have considered differently. He pointed me specifically towards having students consider their own biases and how they might seek out perspectives that were outright different than their own to expand their understanding on an issue. The second time was with a close friend who works for a major national newspaper. He came to speak to my students about his profession and practice of being a journalist and while my students were sharing with him their topics, he instantly noted that they might not be actually newsworthy. A ha! Great feedback. Since I am not a journalist, working with people in the field who know the practice intimately, helped me develop my understanding of the genre. Learning is social. Writing is social. Making mistakes is social. And we can only grow and get better in relationship with other people.

P: Publishing

All writing has an audience, but writing that is truly transformative, shows that the author is aware of their audience and considers them at all stages. Scholars in the world of writing have shown that writing in any genre is cultivated through many pratices, particularly participating in a discourse community and talking about the text. This time of publishing, when students read each other’s published work, when parents read the class writing, when community members gain access to the articles…this is how young people fully participate in the discourse community of journalism. In many ways, this could be described as participating in democracy.

Interestingly, even in Journalism Schools with more mature writing students than the writers I was working with, the act of authentic publishing was not inherent in every assignment. Students, even ones training to become professional journalists, are not engaging on their own with submitting their work to be published. These opportunities to publish had to be “forced” through the structures of the curriculum in journalism schools, or what are called J-Schools. So if older, more mature writers who are dedicating themselves to becoming writers who publish regularly are not publishing their student writing on their own, of course students in Grade 8 will not. So as teachers, we have to cultivate those opportunities to show students how publishing is a deeply social act and thus incredibly effective way to motivate us towards our best work.

Something I learned the hard way is that not all writing is ready to be published. In that first iteration of the project, I thought that all student writing should get featured in our class newspaper. But some students writing was not exactly meeting the expectations. Maybe you’ve experienced this in your practice? In future versions of this project, I made publishing the writing a reason for young people to work towards the success criteria of the assigment. Some students were ready for this publishing and others needed more time to get there. I think that this is okay. I like the idea of different stages of publishing: perhaps a class newspaper that parents and stakeholders in the class community can have access to is one option. Maybe some strong pieces of writing can be added to the school newspaper if one exists, or if some pieces that need more time they can be added to an online publication later in the year. All students can benefit from the experience of publication and yet it doesn’t need to be done at the same time.

U: Useful Community Collaboration

I want to circle back to this point about distrust of the media. This has been a topic written about at length in the academic research about teaching journalism. While I am not trying to train professional journalists (I’m working with grade 8 students) I think the conversations in the world of J-Schools are worth looking at in terms of what they might give teachers hints about how to consider teaching younger writers. There has been a recent push in the journalism academy for more community based and collaborative journalism. Community based journalism is trying to address the issue of how the media perpetuates institutional racism and traditionally does not do a good job of including the voices of marginalized people. When reporters are connected to communities, volunteering in organizations to form relationships, or reporting on communities that they have access to, greater trust can be formed and more accurate stories can be shared with the broader public. Collaborative journalism asks key stakeholders in communities what stories they want to be covered, and works together to identify credible, often non-elite, sources on these stories. What if something similar could be put into practice on the school level? Young people could spend several weeks volunteering at various local community organizations, getting to know the staff, the purpose, and the communities they serve. Then, they could interview various stakeholders and craft news stories about their work to publish and share with the wider school community. Or what might be possible if students sat down with various groups of people connected with their school (young students, parents, staff members, administration, lunchroom supervisors, volunteers) and truly understood what potential stories existed and who they might talk to to research these stories.

Of course, I am imagining a version of school that could involve field visits and connecting with others outside of cohorts. Call me hopeful for a version of schooling that isn’t not as restricted due to the ongoing pandemic. That said, leveraging social situations to guide students towards a kind of writing is not actually a new thing. One thinker, Mary Chapman, has written about this and she believe that genres of writing arise to fulfill a specific social purpose. Genres are not concrete structures or forms that students need to master, but rather flexible models that arise to address a social need. In this case, the social need is to dismantle institutional racism and tell the stories that people in communities want to read about.

S: Structured Feedback

Another deeply social aspect of any writing, is when feedback is offered. I get that writing typically receives feedback before publication, but not always. Sometimes the most meaningful feedback happens after the grade is given, the drafts are sent in, and there isn’t really any space to change anything. Also, for the purposes of the RUMPUS acronym, strategic feedback needed to go at the end. But in the life of the classroom, feedback may be happening at any time really.

Providing feedback is a key recommendation from the scholarly research about best practices in writing instruction. Feedback from teachers, their journalistic mentors, fellow students, and from themselves are all required to move students forward in their writing skills. Peter Elbow, one of the pioneers of freewriting, has some things to say about writing feedback. In his 1998 text Writing with Power, Elbow delineates two kinds of writing feedback: criterion and reader-based feedback, both of which are important to include in how students get insights about their craft. Criterion-based feedback judges the writing against a rubric, set of success criteria, or checklist and reader-based feedback says what the writing does to the reader. Elbow also suggests to teachers that reader-based feedback is easier to give. So with this writing experience, in small–ideally trusting–groups, students can share with each other their experiences when reading drafts of each other’s writing. When teachers or the journalist mentor are reviewing early drafts of the writing, working from co-constructed criteria gives a different kind of feedback on the writing, which ideally rounds out the reader-based feedback from the peers. This might also look like a structured protocol in a reader response group, modelled with a small group for the whole class to watch before trying it independently.

Learning about how our writing impacts other people through structured feedback is typically the aspect of social writing practices that most teachers include in their writing programs. So likely none of these ideas are a surprise to you. But how you consider reader-based, criterion, or protocoled feedback may heighten and strengthen the inherently social aspects of this practice.

Caller Questions:

So when you are trying to remember what makes journalistic writing so valuable and important, pull up in your head that memory of all those wild things living their best life, or having their wild rumpus: Researching Through Interviews, Unpacking Identities, Mentoring, Publishing, Useful Community Collaboration, and Stategic Feedback.

We are now going to do something totally new for the podcast and take some listener calls. We are going to start with Peter.

Hi Celeste. My name is Peter and I’m calling from Kitchener, Ontario. I’m a grade 9 and 10 English teacher and I actually really hated English classes when I was a student. I got into teaching because of my passion for teaching drama, but the school I am in right now only has me teaching English. I struggle as a writer myself and I always feel like I am just re-creating the boring assignments my teachers made for me…but I don’t really have any other strategies in my toolkit. I’m also just more tired than ever and I’m finding it hard to push myself to get better as a writing teacher. What suggestions do you have?

Ugh! I so feel you Peter! And I want to just start by saying that you are not alone in this. I mentioned earlier that the research points to the fact that teachers do not feel prepared by their teacher education programs to teach writing, so even if you did have an English undergrad, I wouldn’t be surprised if you also felt similar things.

Something else that is clear in the research about top recommendations that improve writing is that we need to have supportive writing communities to help us as writers. Writing is a social practice, after all! I hope you are starting to feel that after listening to this episode.

One of the most powerful writing experiences I have had as a teacher was when I got to participate in the week-long Institute for Writing and Thinking with Bard College where teachers were guided through writing practices, so that we could facilitate these experiences with our students in the classroom. Even though I enjoy writing, I also have a drama undergrad and I have always kind of worried that I didn’t know enough about how to teach writing because I didn’t have the same writing experiences as my friends with English majors. So if you can find a way to participate in a Bard program, I highly recommend this. If it’s not possible, I would also point you towards the Toronto Writing Project. There are regular teacher writing workshops that are free and all offered over Zoom (one of the good things to come out of the pandemic). They focus on poetry writing, but regardless of the kinds of writing you do with your students, finding a community of writers to surround yourself in is a key way to feel more confident and become more capable as a writer. This is true for our students and this is true for us as adults and teachers of writing.

Hey Celeste and the Teaching Tomorrow community. My name is Julia and I’m calling from Kingston. I teach middle school English and Social Studies and I’m calling about a dilemma in my practice. I am often having my students write various things across the curriculum and they are receiving ample feedback from myself and my peers. But I am stuck in regards to how I can best teach my students various writing techniques. By the time my students enter grade 7, they know the basic skills, they are comfortable with the thinking processes of writing, but at times there are elements of writing that need to get taught and practiced. Do you have any ideas for how to include direct instruction in a way that is not soul sucking and boring?

Hi Julia. I get this. And in the spirit of leveraging student’s social learning, I think we can actually use this to help with those moments that we need to teach specific writing strategies. Whenever I have used supportive writing groups throughout my classes, I am always grateful for all the early-in-the-year community building work that sets the foundation for students working and learning together. Something that the research on top recommendations for teaching writing suggests is to have students compose together. A perfect idea for supporting students to learn socially! So you might teach a mini-lesson on, say, paragraphing. And I mean mini–think 10 minutes or less–and then students in small groups (3 or 4) can compose something together that applies these new skills. I’m picturing students using that big chart paper and different markers for each student. Students composing together is a good example of a gradual release of responsibility and it is fun for students to work through new skills when learning from and with their peers. Let me know how it goes if you try it in your practice.

Hello. My name is Quinn and I am an instructional coach in Toronto. A few of the teachers I work with have crafted these rich, interesting, and engaging projects for students to learn through, but I see a real need and desire for students to make an impact on the world. With more young people getting involved with climate justice, for example, I feel like there is a perfect opportunity for something deeper. Do you know what other teachers are doing to marry social justice with writing standards?

This is an awesome question Quinn. I’ve been thinking about this a lot. I’m going to use the example of journalism, as that is what I’ve been focusing on with this episode.

When students are writing in this genre, they are aiming to share the facts in a balanced, unbiased way…or at least in a way that accounts for their biases and include diverse perspectives. But once students have learned more deeply about an issue that they care about, the natural extension is to consider what they might do to design other possible realities. There is a lot written in the world of critical literacy that gives us some ideas of what this might look like. If you want to read more, I highly recommend checking out the writing of Hilary Janks or Vivian Vasquez.

After the news articles have been published, students could be invited to choose another genre or mode of creation to leverage this heightened awareness. Students could write a letter to petition someone in a position of authority to make policy change, to create a PSA video for their school social media account to educate about an important issue, to design a new space in their school community to address an unmet need from their students (perhaps a garden, a quiet corner, a snack bar, a positive affirmation mirror), or write a story that reimagines a more desirable future in regards to a complex issue. We often think that publishing is the final stage of the writing process, but I think actually the final stage is doing something with the knowledge we have gained. Taking the writing and then reimaging it to create difference. The journalistic writing could be the vehicle for researching, learning about the multiple perspectives and stakeholders on an issue, and then the next project could be requiring students to apply their newfound learning to make a change in their communities. You can probably tell that I’m really excited about this, so if you end up running with this, I hope you will loop back and share your learning with us.

Thanks folks for calling in and sharing your questions about your teaching practice. I always love hearing from you, so if you have a question or a dilemma that you want some research perspective on, send me a voice memo to [email protected], hit me up on Instagram @teaching_tomorrow or find me on Twitter @teach_tomorrow.

Before we close off, I want to come back to my friend Annie. We all know students like Annie: bright, capable, thoughtful, full of potential. And they keep us up at night because we know something is not quite right about the systems of schooling for them and as a result, they are not thriving. The bigger system of schooling is not going to change itself. It is is up to us. The Ministry of Education Language Arts documents have not been updated since 2006. 2006! Maybe if they had, there would be more included about the social practices and sociopolitical aspects of writing and students like Annie would find themselves more easily in our programs. But maybe not. It is up to us teachers with whatever power we have to tweak, challenge, redesign, and reimagine our programs to be more socially oriented to better meet the needs of our students. I hope for Annie’s sake we can.

That’s all the time we have for today folks. Keep writing inside that wild rumpus and remember we are teaching tomorrow.