In my last post, I wrote about my aspiration of developing a culture of thinking in my students. But what thinking actually mean? Today’s readings and session with Dr. Kelley Nicholson-Flynn focused on just that.

I have done a LOT of reading over the past two days, but the one piece that stuck out the most for me has been Why Students Don’t Like School: A Cognitive Scientist Answers Questions About How The Mind Works and What It Means for the Classroom by Daniel Willingham.

The except from chapter one starts off explaining that people are naturally curious, but we are not naturally good thinkers; unless the cognitive conditions are right, we will avoid thinking. So how will I ever achieve my aspirations of developing a culture of thinking in my students if their minds physically designed to avoid thinking?

Thinking requires reasoning, whereas memory does not. However, often in traditional education, a disproportionate amount of energy has been spent by students on memorizing information for tests. If we want to train our kids to think, then why do we design assessments and evaluations that require them to memorize information? One could argue that this practice is increasingly irrelevant in the 21st Century, when ostensibly all information is available on the internet and can be accessed via a smartphone. Should our assessments focus more on giving students the information they require (or allowing them to look it up) and requiring them to demonstrate their thinking skills? This is not to say that students do not still require factual knowledge. For example, they must know what sustainability means in order to evaluate whether or not something is sustainable. However, perhaps if they spent less time and energy on memorization they would have more time to develop thinking skills.

At Greenwood, teachers aim to personalize learning for students both on readiness and on interest, which according to cognitive science are excellent factors for motivating students to learn.

When developing assignments, Greenwood teachers often give their students choice. Choice could come in the form of the choice of book to read, the choice of a topic for an independent study project, or the choice of a path through a unit. Students are encouraged to follow their own interests. However, Willingham points out that while interest in the content will spark motivation, interest alone will not sustain motivation. The answer lies in the difficulty of the problem itself.

Willingham highlights the paradox of thinking. Even though our brains try to avoid it, at the same time the brain finds pleasure in thinking. He cites a study that showed the brain releases dopamine, the same chemical that is connected to the brain’s pleasure system, when a person successfully solves a puzzle. However, he notes that the pleasure comes in solving the problem, without too many hints. Therefore, the key to motivating our brains to think lies in assigning problems that are just the right level of difficulty. Too easy, or too hard, and motivation is lost. In other words, we must meet students where they are, with a challenge that interests them, and then nudge them to move forward a little at a time, finding success along the way.

Willingham highlights the paradox of thinking. Even though our brains try to avoid it, at the same time the brain finds pleasure in thinking. He cites a study that showed the brain releases dopamine, the same chemical that is connected to the brain’s pleasure system, when a person successfully solves a puzzle. However, he notes that the pleasure comes in solving the problem, without too many hints. Therefore, the key to motivating our brains to think lies in assigning problems that are just the right level of difficulty. Too easy, or too hard, and motivation is lost. In other words, we must meet students where they are, with a challenge that interests them, and then nudge them to move forward a little at a time, finding success along the way.

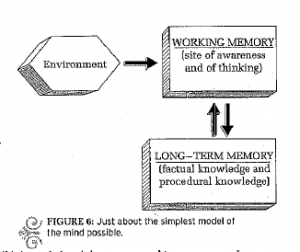

To sum up, Willingham explains, “For problems to be solved, the thinker needs adequate information from the environment, room in working memory, and the required facts and procedures in long-term memory.”

One example of this in action comes from a talented colleague who encourages students to practice thinking and reasoning. He often starts his classes with a riddle for students such as “Democracy is to Human Rights what ________is to summer.” He is asking his students to flex their mental muscles by deducing, reasoning and then explaining their choice to a peer. This process helps students develop the skill of thinking – which just like taking a free throw in basketball or landing a plane, or making tough decisions about life, requires practice.

The Psychology of Learning

So, how can we apply this science to our classrooms? Dr. Nicholson-Flynn discussed several ideas for motivating students, including:

- Behaviourism (reward/punishment based on behaviour)

- Intrinsic Motivation

- Congnitive Pshychology

- Growth Mindset

- Stereotype Threat

- Character Strengths

The pieces that I found most compelling were on Growth Mindset and Character Strengths, as developing these traits are included in both my personal goals and the goals of Greenwood.

I believe that in order to develop a Growth Mindset in students, we must encourage them to find value in failure, set high standards, provide positive reinforcement and require reflection. For example, at the beginning of this year, while working on a landscape plan for the Lower Don Lands, one of my grade 12 students blurted out “I suck at this!” Julian was frustrated because there were other students in the course who had better natural drafting skills, or who had more experience in drawing. He was comparing his work to theirs and wanted to give up. However, at the same time, it seemed as though he was motivated by their success – he set a benchmark for himself and wanted to improve. So, he took home extra paper and base plan drawings and worked through several iterations of his plan over the weekend. He came back on Monday with a drawing that was technically much better. However, the design itself still required work. He didn’t fully address all the criteria for the design because he was caught up in the skill of drafting. I provided feedback on his design and while he was disappointed by the results, he saw how much he had improved the drawing component of the assignment and therefore was encouraged that he could also improve his design skills. Later in the year, on his culminating activity, Julian produced a landscape plan for Ontario Place that was not only technically well drawn, but also met all the criteria for the design and included thoughtful details related to concepts in urban planning that we had studied. While completing this design, he blurted out in class “I love this! I wish I could do it all the time!” I pulled out his first drawing from the beginning of the year and asked him to describe to me how much he had improved. He expressed confidence in his ability to learn a new skill and to develop a love for something that he thought he hated.

This anecdote shows that students are capable from moving beyond a fixed mindset. He was able to do so by persevering, having small successes along the way that allowed him to reflect on his learning, and receiving positive reinforcement from me, and having high standards for success set by his peers.

Perseverance was a key component in Julian’s success. Last week in Greenwood’s Professional Learning Communities (PLC) group presentations, Garth introduced us to Angela Lee Duckworth’s work on developing “grit.” Their PLC group completed Lee Duckworth’s Grit Survey and Garth suggested that we watch her TED Talk on the subject. She believes that in order to improve student’s success in life, we need to better understand what compels students to develop “passion and perseverance for long term goals.”

Perseverance was a key component in Julian’s success. Last week in Greenwood’s Professional Learning Communities (PLC) group presentations, Garth introduced us to Angela Lee Duckworth’s work on developing “grit.” Their PLC group completed Lee Duckworth’s Grit Survey and Garth suggested that we watch her TED Talk on the subject. She believes that in order to improve student’s success in life, we need to better understand what compels students to develop “passion and perseverance for long term goals.”

Dr. Nicholson-Flynn also talked about Lee Duckworth’s philosophy on grit, sharing the same studies. Furthermore, she shared with us a study on the qualities that have been shown to be indicators of success in life. The indicators of success were tied to academic success, but rather character traits:

- social character – interpersonal self control, gratitude, social intelligence,

- intellectual character – zest and curiosity

- achievement character – grit, self control with work, optimism

At Greenwood, we talk about achievement character as performance character and we divide social character into moral and civic character. Whichever framework is used, it is clear that developing these traits in young people needs to be as important, if not more important than simply preparing them for academic success.

However, so far, neither Dr. Nicholson-Flynn nor Lee Duckworth have an answer on how to develop grit in students. Tomorrow, Dr. Nicholson-Flynn will be back to speak with us again, and my question for her will be: How do we successfully develop these traits in young people? For example, does pushing students beyond their perceived limits help to develop grit? What can we do outside the classroom to nurture these characteristics? For example, does outdoor education really improve perseverance? Can service learning develop moral character? How?

Wow. Thanks for such a fantastic, detailed account of some of your take-away learnings from Kling so far. Keep them coming; it is so lovely to get to live vicariously through your writing.

I went to High Tech High in March this year with a very similar question. I wanted to know how to explicitly teach a growth mindset, not just talk about it or teach around it.

One key insight I gained was that the skills of a growth mindset can be broken down into different habits / skills / practices. Habits of mind work well as a way to articulate these, but others do the trick as well. We have “learning skills” as part of our assessment practices at BSS, so it made sense to use these as a guide.

Once you know the “habits” you want to teach, they can actually be embedded in your assessments and projects. I just had my students doing a blogging project, and I was explicitly teaching them “self-regulation”, as a step closer towards a life-long growth mindset.

Here is some writing I did on it: http://cohort21.com/ckirsh/2014/03/14/making-assessment-planning-as-yummy-as-cookies/

I’m looking forward to hearing what KNF has to say on this as well. Be sure to update this story if you have the time between the mountains of reading you are doing!