In the Rob Reiner film “A Few Good Men”, the climax of the movie comes when Lt. Kaffee, played by Tom Cruise, puts his arch nemesis, Col. Jessep, played by Jack Nicholson, on the stand, hoping to coax a confession from him. The exchange is made famous by the following dialogue, written by Aaron Sorkin:

Jessep: You want answers?

Kaffee (Tom Cruise): I think I’m entitled to them.

Jessep: You want answers?

Kaffee: I want the truth!

Jessep: You can’t handle the truth! Son, we live in a world that has walls. And those walls have to be guarded by men with guns. Who’s gonna do it? You?

The Colonel in this case holds a truth that he doesn’t feel Kaffee, a man he sees as an inferior, is worthy of knowing or understanding. Here lies a problem that I see in my own classroom (and perhaps one that exists in many others): the tired dogma that the primary relationship between teacher and student is one of power — the teacher decides what the ‘truth’ is and who gets to understand or receive that knowledge. That power stems from a simple fact, one that I knew all too well as I tried to copy every board note I could before my old history teacher would erase what was there and move on to the next topic: teachers have the knowledge and students do not. Whether it’s in politics or in the classroom, knowledge is power, and whoever holds that sacred ‘truth’ rules the world.

This year I’d like to challenge that concept in my own classroom. In my early days of teaching I was terrified if I were revealed to be the fraud that I felt I was, revealed to not have the answer. With experience, I’ve come to learn that the greatest dividends for student learning happen when students feel empowered, when they feel heard, and when they understand what I want them to do. But this last part represents my current focus, ‘when they understand what I want them to do’. What if they were able to display their understanding using a method that best suits their strengths, their personal learning style? What if a student could decide what matters? Armed with a curriculum, the basic criteria of evaluation, would a student be more fully engaged, more passionate and, ultimately, more successful, if they were the ones to determine what their ‘truth’ is?

In grade 12 English at Trinity College School, I am currently teaching a semestered course focussed solely on short fiction. After reading two Sinclair Ross stories, students were let loose with a list of Canadian authors and a hefty Canadian fiction anthology, encouraged to choose a story that spoke to them in some way. The class understood the primary enduring understanding of the unit was to explore the dominant themes in Canadian fiction, but how they ‘explored’ that landscape was up to them.

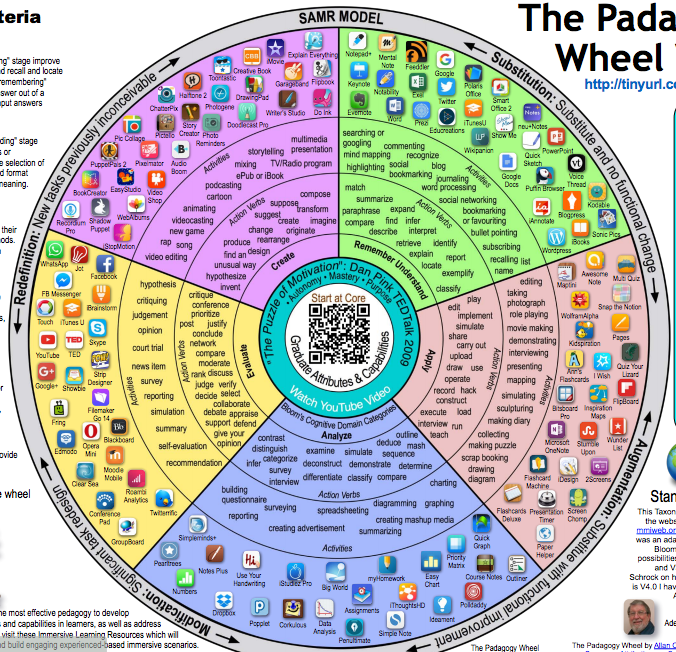

Thanks to @ddoucet I showed students a Pedagogy Wheel that displayed the relationship between the SAMR and Blooms Cognitive Domain Categories. Students were given the criteria for the assignment, and they were asked to choose what method of presentation best suited their style of learning. The most common response was, “I have no idea!”.

Isn’t this an important duty as educators, to ensure students understand what they are good at, before leaving for university?

Today students worked collaboratively to build their rubric for this evaluation. Conferencing with students it became clear they had never been given this type of ownership over their own learning before. The question is this: will it produced the desired results? Will student performance, understanding, and authentic appreciation for the material be improved when they build the unit from the ground up? Hopefully, if we focus on digging down to the core ‘truth’ of the story, for each individual student, then the answer will be yes. Rather than listening to their teacher lecture to them about what he feels is the important symbol or the key piece of dialogue, students will make that determination for themselves and show that knowledge with a means that best suits their personal learning style.

I hope to dig deeper on co-construction and personalized learning this year. I have more questions than answers, but as Lt. Kaffee tells Col. Jessep, I don’t want answers, I want the truth! (lame ending, I know:)

We said, Brent. This line resonates most of all with me:

With experience, I’ve come to learn that the greatest dividends for student learning happen when students feel empowered, when they feel heard, and when they understand what I want them to do.

Awesome post Brent Hurley, so happy I stumbled upon this read this morning. And what a wonderfully noble endeavour! I think your question – “will it produce the desired results is a good one” – but, as I’m sure you know, the approach/idea (co-construction, voice and choice, personalized learning, etc…) is not enough. I say this only because of my own tendency to become in love with, and over-romanticize, my ideas. The students don’t always share that love which is always a little heartbreaking – I think particularly if they’re not used to learning in this way, and maybe even more-so if they’re in grade 12. You are initiating a culture shift! Your endless enthusiasm and intentional process will be the driving force of success – this could be a feedback cycle of proposals and revisions and private conferencing. A really powerful approach is to create alongside and to also present. It’s pretty awesome to have a colleague run some form of a design thinking lab for you and your students to participate in at once.

I think it’s also important to keep these initiatives in perspective with your first question: “Isn’t this an important duty as educators, to ensure students understand what they are good at, before leaving for university?” The reflective process after the experience is perhaps more important than the outcome of the project.

I hear Graham’s concern that the students will not be as excited about personalized learning as their teacher. The reality of students just after the grade is true…but we are the experts (even if we don’t know everything) on education and what you are attempting is important far beyond the curriculum you are serving. Teaching your students about their skills, talents, and passions (on top of Can Lit) is something I think they will know and understand long after your course is done. You almost need to do a 10 year follow up on this one (put that in your calendar)!

@brenthurley Way to go! Inspiring @gvogt and @ckirsh to drop some gems into this conversation and push some great ideas forward. Also nice to see Myke Healy jump in here. It means your ideas are being read by those outside of the Cohort as well.

Back to your post……

I think one way to translate the student statement of “I have no idea!” is to read it as “I have had little practice doing this”. The reality is this pedagogical approach to giving students choice in the way they communicate their understanding is not a common one. They simply have not had many opportunities to struggle this way.

I challenge you to apply this framework several times throughout the year and see if there is growth. Get them to reflect on what was difficult and what they would have done differently. See if it moves the needle a little. #perfectactionplan

@lmcbeth @gnichols @ddoucet @rutheichholtz @jenbibby @jweening @shelleythomas

@bhurley –

I love this. My favourite line: “Hopefully, if we focus on digging down to the core ‘truth’ of the story, for each individual student, then the answer will be yes.”

Like you said, education has become primarily the imparting by teachers of “truth” upon students. In literature especially, how can we ever say that there is one “truth”? Sure, there are trends and themes, and parts of speech and all those other things, but is not the power of literature to speak truth in different ways to different people?

I can’t wait to hear how this experiment continues to unravel!

Fantastic! This post has opened my eyes up to some great ideas for my own classes.

I have just started to present my French students with a similar task where they have been asked to demonstrate their learning in different ways. I have was initially offered similar responses: “I have no idea”. But with some direction, I have been impressed with what I have seen thus far. My hope is to have it much more open by the end of the year. I had never seen the Pada wheel before, so that is definitely something I will try to integrate.

I have also been experimenting with personalized dictionaries in French class (which could maybe be applied to English as well) and testing them on what they have felt is most valuable for their own language development. So far it has been really successful.

I still have many questions for this type of learning, so, like Jen, I look forward to hearing more about your experiments!