The idea that modern computer/digital technology brings with it benefits and advantages is obvious. This is the sort of truism that is embedded in my Latin and history lessons every day, when we talk about chronology and change. While I certainly believe that this idea is true, I also recognize that technology has (or is in the process of) effecting changes that we do not yet fully understand and which, I would argue, are not necessarily changes for the better. I am thinking here of the unintended consequences that emerged as a result of a whole-hearted embrace of coal-powered technology. While this technology revolutionized and improved many aspects of life, it also had effects and consequences that, upon reflection, were not beneficial. Some, like acid rain, became obvious. Others, like the underlying model of order and uniformity imposed by the factory model, were and are more subtle. In the case of digital technology, we are becoming aware of what the “acid rain” consequences are: cyber warfare and espionage, cyber-bullying, etc. What I am interested in, however, and what I will spend this year focussing on, is one of the many more subtle, often broader consequences of a digitized world for communities and learners: is the immersive, expansive, fast-moving digital world eroding a person’s ability to slow down and focus on one thing at a time? Research suggests that reading from a screen causes neural pathways to form in ways different from when reading is done from print sources. Are we also changing our brains by exposing them to constant stimulus? What brought me to these musings was a chance encounter with students using a “how fast do you read” app on the internet. When I saw their results (1000 words per minute), I was skeptical. How could anyone read that fast? I asked a few follow up questions to see if they had just said they had read that fast. The students were able to answer broad, general questions about the passage as a whole, suggesting they had read the passage. But when I asked more specific questions, questions whose answers would be found in specific sentences, they were stumped. This prompted me to ask what their reading approach was. They revealed that they read the text (part of a novel) the way they read blogs, websites, etc.: quickly and by scanning for key ideas, names, facts, etc. They suggested that, with so much to read, they had gotten used to not reading every word in every sentence. This chance encounter led me to want to learn more about what is going on. Are our students changing because of technology? The initial observations (including those from other contexts) seem to suggest that a new form of reading and attending to detail is emerging, one in which meaning is constructing by observing chunks or swaths of information. What I really want to know, however, beyond what we are gaining by having learners and citizens who can harvest meaning from huge amounts of data, is what we may be losing by not paying attention to the details, to, as others have put it, “think slow.”

The idea that modern computer/digital technology brings with it benefits and advantages is obvious. This is the sort of truism that is embedded in my Latin and history lessons every day, when we talk about chronology and change. While I certainly believe that this idea is true, I also recognize that technology has (or is in the process of) effecting changes that we do not yet fully understand and which, I would argue, are not necessarily changes for the better. I am thinking here of the unintended consequences that emerged as a result of a whole-hearted embrace of coal-powered technology. While this technology revolutionized and improved many aspects of life, it also had effects and consequences that, upon reflection, were not beneficial. Some, like acid rain, became obvious. Others, like the underlying model of order and uniformity imposed by the factory model, were and are more subtle. In the case of digital technology, we are becoming aware of what the “acid rain” consequences are: cyber warfare and espionage, cyber-bullying, etc. What I am interested in, however, and what I will spend this year focussing on, is one of the many more subtle, often broader consequences of a digitized world for communities and learners: is the immersive, expansive, fast-moving digital world eroding a person’s ability to slow down and focus on one thing at a time? Research suggests that reading from a screen causes neural pathways to form in ways different from when reading is done from print sources. Are we also changing our brains by exposing them to constant stimulus? What brought me to these musings was a chance encounter with students using a “how fast do you read” app on the internet. When I saw their results (1000 words per minute), I was skeptical. How could anyone read that fast? I asked a few follow up questions to see if they had just said they had read that fast. The students were able to answer broad, general questions about the passage as a whole, suggesting they had read the passage. But when I asked more specific questions, questions whose answers would be found in specific sentences, they were stumped. This prompted me to ask what their reading approach was. They revealed that they read the text (part of a novel) the way they read blogs, websites, etc.: quickly and by scanning for key ideas, names, facts, etc. They suggested that, with so much to read, they had gotten used to not reading every word in every sentence. This chance encounter led me to want to learn more about what is going on. Are our students changing because of technology? The initial observations (including those from other contexts) seem to suggest that a new form of reading and attending to detail is emerging, one in which meaning is constructing by observing chunks or swaths of information. What I really want to know, however, beyond what we are gaining by having learners and citizens who can harvest meaning from huge amounts of data, is what we may be losing by not paying attention to the details, to, as others have put it, “think slow.”

I am, strangely enough, well-placed to test out this hypothesis and observe the results. As a Latin teacher, I work with a language that demands attention to detail. As an inflected language, students must pay attention to detail. Each word has layers of meaning that must be attended to, at first slowly, but eventually with speed as experience grows. I have already seen over the last few years that students between the ages of 13 and 16, therefore born after the year 2000, recognize inflectional differences (i.e. details) much more slowly than students born in the 1990s that I taught when I was at Queen’s. Indeed, students here at UTS seemed surprised that they would even need to focus on individual words and that individual words could be that important. To be sure, it would be easy to overstate the importance of technology in what I have observed. Surely, every older generation has looked at the upcoming generation and thought that what that new generation was doing was a bit slower, or a bit less proficient. What I am contending, though, is that, at the very least, technology may be making it less likely for students to attend to detail, to slow down and think carefully about specifics. I am also suggesting that it is and will be more important than ever to teach students explicitly the importance of attending to detail and ‘thinking slow’.

My work this year, then, will be determine what sorts of interventions and scaffolding I can put in place in a Latin classroom to help students attend to detail and think carefully. I will need to read more of the latest research about the neurological implications of technology, as well as about the best brain-based pedagogy currently out there that could make a difference in countering the current produced by immersive, omnipresent tech that seems to pulling our students farther away from careful, detailed study. I will also benefit, appropriately enough for an historian, from learning about methods from the past that were meant to help students slow down. Surely, adolescents of every generation have had to be taught to slow down when thinking or reading, and so I know those past pedagogues will have resources to share with a colleague from the future grappling with a similar problem.

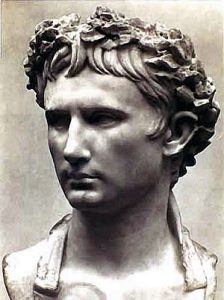

My goal, then, will be to help students confronted by an immersive, fast-paced digital world do what the Emperor Augustus once did: festina lente! Move quickly, but in a slow, deliberate, methodical, and careful way. I can’t wait to see where this project takes me, this year and for years to come!

I have seen a number of articles in the past year lamenting the fact that students no longer really read longer texts. What I find frustrating as a teacher, even as a math teacher, is that my students are less capable of producing text themselves. They don’t proofread, they end paragraphs mid-sentence, they allow spellcheck to insert words that are out of context.

I look forward to seeing what your research turns up this year, as I would be interested in adopting strategies to help students slow down, think, and pay attention to detail. Learning Math is also learning a language, and the skills required are similar, don’t you think?

Hi Chris,

I find myself lamenting the distractions of technology all the time, at an essentially paperless school – I didn’t even use the printer until halfway into October! It can absolutely be a struggle to get students to look each other in the face when they are interacting, and I sometimes find myself wondering how there can be space for spontaneous and authentic communication unless their laptops are completely closed, which is what I often have to insist upon.

Also a language teacher here, and I contend with the ever-present quick fix of Google Translate. “But I’m just looking up one word,” they cry…

One observation I have made related to this topic is that students have trouble tolerating even 30 seconds of wait or transition time. They always have tens of tabs open in their browser or OneNote, and I must control my frustration when I see that they are getting in 10 seconds here and there of finishing their overdue math homework, when they are in MY French class!

That’s an incredible anecdote about the speed-reading test. I would be so interested to see if there has been any science done on this phenomenon yet!

Thank you for the thought-provoking post,

Irena Snefjella

Oops, forgot to tag anyone! The language teacher in my home group: @kellycarlson, @mackenzieneale, @myriamlafrance, @thomasjohnstone – my apologies if I left anyone out, I haven’t met you all yet!

@kcarlson, @mneale, @mlafrance, @tjohnstone – What do you folks find has been your experience, as language teachers, with this tendency of students to skim texts? I think this might be part of the reason I hear the question so often – “do I really need to include all the accents?” Um…

There we go, I think that tagging finally worked! Sorry, Chris, for using your blog post as my trial-and-error arena for my Level 2 blogging :p

Thank you Chris for such a thought provoking blog! I love your critical look at tech and how people consume information online. I think we all recognize attention spans and attention to detail are aspects of learning that some students struggle with. In a recent design think with my French class we explored “how might we motivate people to want to learn a language” and they came up with the general ideas of trips and games and what we might expect but it was in the next class when we used a Connect, Extend, Challenge routine that pushed them beyond the surface and how we might effect real change in plurilingualisme in Canada – perhaps students in general – are used to getting an assignment that tells them what they need to do and every product looks the same so that deep connection and attention to detail is lost because they have no ownership over their learning? I am really looking forward to hearing more about your action plan and how it evolves over the day tomorrow!

That sounds like a great activity to get the kids thinking about if and how they are engaged in language learning. The ironic part about all of this is that language learning is, and really must be, a personal, intimate, individualized process. That’s not how these classes have been designed traditionally, but it’s something that technology will hopefully help us do. With DuoLingo, for example, we can know EXACTLY what students can/can’t do, the words they WANT to learn, the structures they WANT to practice more with, etc. That’s not possible in the status quo, and I’m very excited for what lies ahead. What’s needed in this bold new frontier, as I said in the blog, is to layer old some good, ol’ approaches to slowing down and attending to detail. I’m not suggesting a sensory-deprivation chamber in our language classes, but with our current and upcoming generations, a sort of conscious and deliberate ‘unplugging’ and ‘intervention’ may be needed! @ddoucet

Hey Chris,

Fascinating to me that you are teaching Latin. Loved your post, and your determination to understand this unfolding generational trait. I’m sure you’ve probably read or at least looked at Daniel Kahnenam’s book “Thinking Fast and Slow”. Here’s a review of it here:http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/27/books/review/thinking-fast-and-slow-by-daniel-kahneman-book-review.html

My mother (a life-long teacher) talked to me about how she was taught “speed-reading” in University. I find it ironic that now we may need to teach “slow-reading”. Can’t wait to see what your Action Plan reveals.